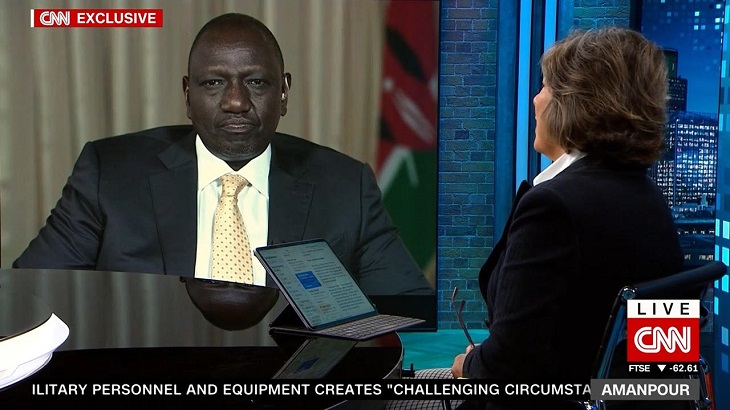

In its latest feature on Kenya, The Economist paints a grim and frankly one-sided picture of President William Ruto’s leadership, accusing him of leading the country down a “dangerous path.”

While sensational headlines and pessimistic takes may serve Western media’s appetite for controversy, they do little to reflect the reality on the ground in Kenya—a reality that is far more nuanced, dynamic, and, importantly, hopeful than what the article portrays.

To read The Economist’s piece, one would be forgiven for believing that Kenya is teetering on the edge of political and economic collapse. The article conveniently cherry-picks facts, omits key context, and disregards the tangible progress being made across various sectors under President Ruto’s leadership.

Worse still, it presents recent protests as purely organic expressions of public dissatisfaction, failing to mention the disturbing infiltration of these demonstrations by organized criminal elements and political saboteurs.

Let us be clear: no government is above scrutiny, and criticism—when rooted in fairness and fact—is both welcome and necessary in a functioning democracy. But what The Economist offers is not an informed critique; it is an oversimplified and lopsided narrative that ignores the full scope of Kenya’s political and socio-economic landscape.

Perhaps the most glaring omission in The Economist’s article is the complete absence of mention of President Ruto’s transformative development agenda. Since taking office, Ruto’s administration has embarked on a wide range of ambitious programs aimed at economic empowerment, food security, digital innovation, and affordable healthcare.

Under the Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA), President Ruto has prioritized the empowerment of ordinary Kenyans—especially the youth and small business owners—through initiatives like the Hustler Fund, which has disbursed billions in microloans to previously unbanked individuals. These funds are not just a political gimmick, as the article would have you believe, but a deliberate economic intervention aimed at creating liquidity and resilience among the informal sector that employs over 80% of the Kenyan workforce.

Moreover, the government has significantly invested in agricultural subsidies, fertilizer distribution, and irrigation schemes to combat food insecurity. The Galana Kulalu project, long abandoned by previous regimes, is now being revived to make Kenya more food-sufficient. Infrastructure development continues across the country, with roads, affordable housing projects, digital hubs, and renewable energy investments taking root in counties that were long marginalized.

Yet none of these critical developments found space in The Economist’s narrative.

The recent protests in Kenya, ostensibly about the Finance Bill 2024, are framed by The Economist as an inevitable outcome of government arrogance and economic mismanagement. This interpretation is not only simplistic but also irresponsible.

While it is true that many young Kenyans were genuinely expressing frustrations over the rising cost of living and the proposed tax measures, it is equally true—and now widely documented—that these protests were infiltrated by criminal gangs and rogue political operatives who sought to hijack the movement for nefarious ends. Government buildings were vandalized, businesses looted, and even parliament was stormed—not by peaceful demonstrators, but by organized thugs armed with crude weapons.

Any credible media outlet must distinguish between legitimate dissent and orchestrated anarchy. By failing to make this distinction, The Economist unwittingly (or perhaps intentionally) legitimizes criminality and delegitimizes the government’s responsibility to protect life and property. President Ruto, in response, withdrew the Finance Bill and committed to more inclusive dialogue—actions that reflect flexibility and leadership, not authoritarianism.

What is also deeply troubling is the continued tendency by Western media, including The Economist, to evaluate African leaders through a condescending lens of “democratic purity” that they do not apply elsewhere. The same media outlets that downplay mass protests in European capitals or racial unrest in America are quick to brand African governments as despotic at the first sign of unrest.

This double standard is not only unfair but also dangerous. It undermines the legitimacy of African institutions and trivializes the efforts of African governments trying to balance the competing demands of development, democracy, and global economic shocks, many of which are not of their own making.

It is time that reputable media outlets like The Economist rise above the temptation of gloomy, clickbait narratives and commit to more balanced journalism when covering African countries. Kenya is a democracy, and like all democracies, it is undergoing growing pains. But under President Ruto’s administration, the country is making genuine attempts at economic transformation, youth empowerment, and technological innovation.

To overlook all this and cast Ruto as a villain, steering Kenya into ruin, is not only unfair—it is dishonest.

Kenya, like any nation, deserves to be critiqued. But let the criticism be anchored in truth, balance, and context, not in bias, omission, and convenient oversimplification. The path Kenya is on may be challenging, but it is certainly not dangerous—unless, of course, the danger lies in The Economist’s inability to see beyond its narrative.

Related Content: If There Is No Country For William Ruto, There Is No Country For You